The past decade has seen political polarisation, exacerbated by social media's filter bubbles and echo chambers, deepen and mutate across the globe, fromSouth KoreatoFrance. But now the era of apolycrisis, marked by rising income inequality and widespread economic anxiety and insecurity, is shattering any remaining social consensus. Fromgentrification pushbacksto violent riots, disenfranchised people are turning to both fringe andconventionalvoices andcontentthat risk dismantling the system and elevating the pain caused by structural inequities and economic hardship.

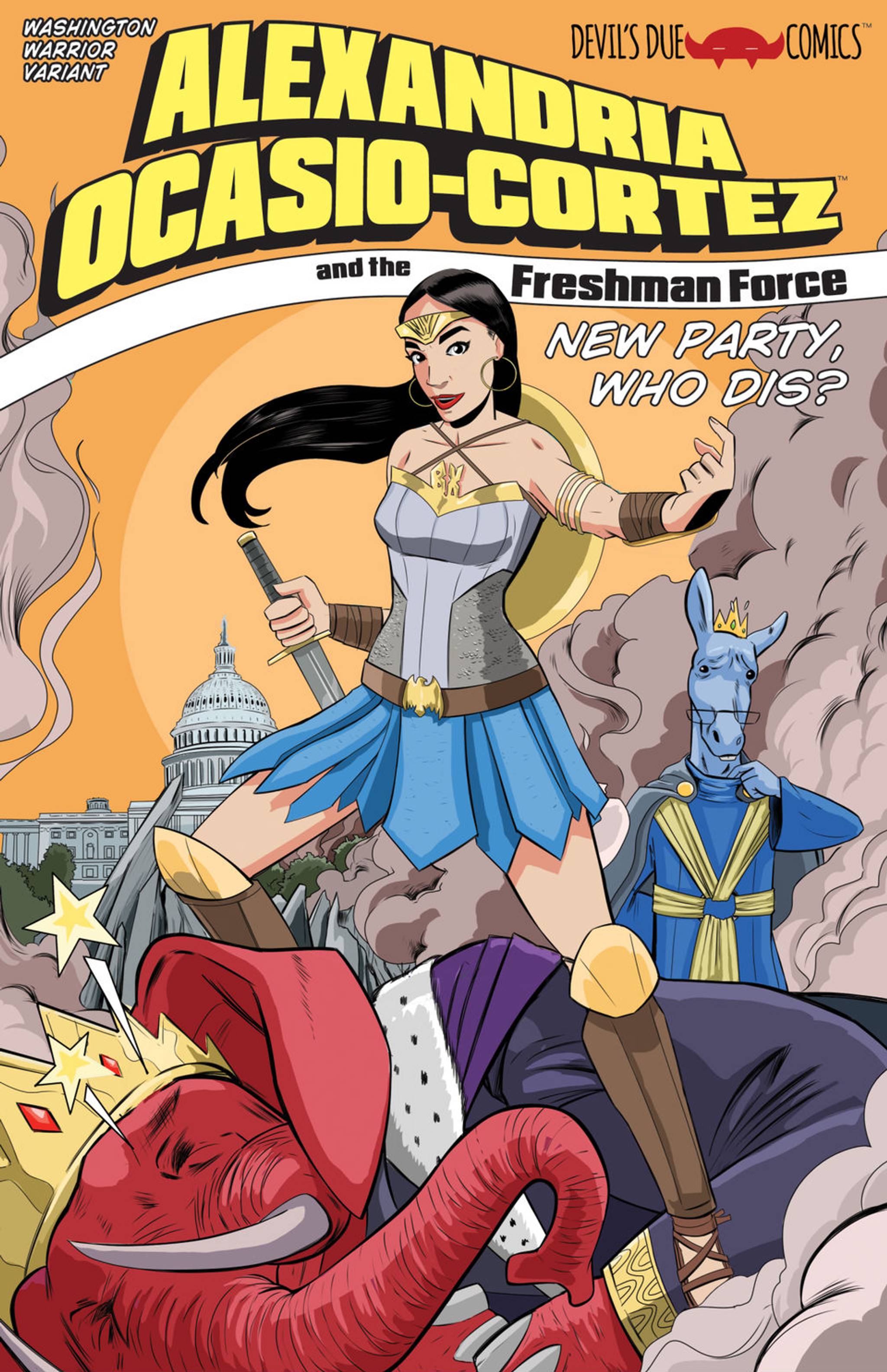

Yet ideological rifts are expanding beyond the confines of politics and economics. Polarisation is becoming an undercurrent that runs beneath everyday life, a defining element of the broader belief systems that determine thepop culturepeople consume, where theylive, where they shop, and who theydate. At the same time, political parties are acquiring qualities better associated withfandoms, with people projecting their desires and fantasies onto leaders and in the process creating distorted images and even fuelling extremism.

In this climate of heightened societal divisions and heated debates about everything fromfashionto regional wars,cancel culturehas emerged as a powerful tool for both social justice and social division. While it can be a means to hold individuals and institutionsaccountablefor harmful actions, it can also be weaponised to silence dissent, promote conformity, and reinforce existing and new biases. As technology accelerates, unchecked AI can also fuelmisinformationand amplify polarisation, leading to a further erosion of trust and a deepening of social fractures.

Simultaneously, a desire for reconciliation is growing. Although some people are drawn todivisive content creators, others are turning topodcasts,film festivals, and playfuldigital personalitiesthat encourage balanced discussions, eclectic humour, and a more nuanced understanding of complex issues.